The Kids Are Not Alright

Pediatric Mental Health Care Utilization from 2016–2021

Released September 2022

Reporting by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and major media outlets signals concerning trends in the mental health of American children. When surveyed, nearly a third of parents indicated that their child’s mental or emotional health had worsened since the start of the pandemic.

However, the evidence is not unified, with some studies reporting declines in the prevalence of certain mental health conditions and events. Apart from CDC reporting from the National Syndromic Surveillance Program (NSSP), research has been limited by small samples, reliance on surveys, data lags, or a limited focus on a specific mental health condition or area of utilization.

To inform public understanding of these important issues, the Clarify Health Institute, the research arm of Clarify Health, is initiating an ongoing investigation of trends in pediatric mental and behavioral health. Leveraging an observational, national sample of health insurance claims from more than 20 million children aged 1–19 years old annually, we observe several important trends in the mental health care of America’s youth from 2016–2021.

Our major findings include:

Our findings align with calls to action by other national stakeholders, including the joint declaration by three pediatric medical societies and the Surgeon General’s advisory around protecting youth mental health. They point to an increasing need to improve data collection and monitoring of the mental health of America’s youth and for clinicians, health systems, and insurers to prioritize addressing the growing crisis of pediatric mental health in the United States.

We assessed mental health services utilization among children with at least one primary mental health diagnosis during the calendar year across nine mental and behavioral health conditions:

Our estimates are case-mix adjusted to account for any sample population differences in age or sex over time.

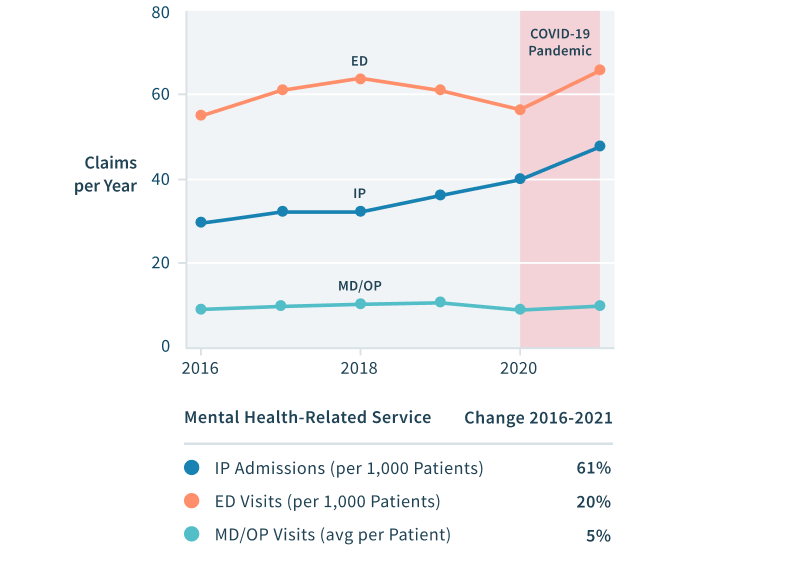

FIGURE 1: Trends in IP, ED, and Office/outpatient (MD/OP) Utilization, 2016–2021

Mental health IP utilization increased substantially from 2016–2019 and spiked during the pandemic

Figure 1 presents trends in the utilization of three categories of health services in the pediatric mental health population: acute IP admissions, ED visits, and MD/OP mental health professional visits. Overall, from 2016 to 2021 we estimate that:

Our estimates are case-mix adjusted to account for any sample population differences in age or sex over time.

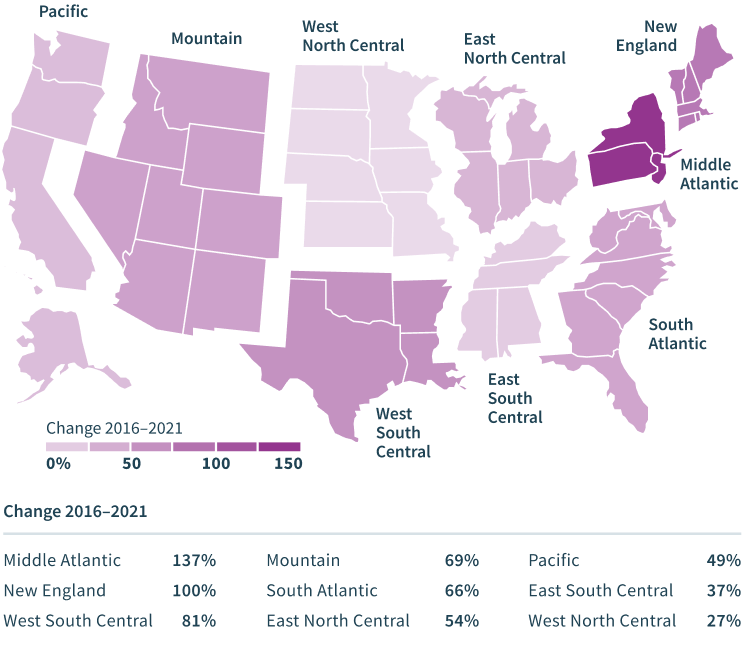

FIGURE 2: IP Utilization Growth across Regions, 2016-2021

Figure 2 highlights regional differences in pediatric mental health utilization and growth. In particular, Middle Atlantic and New England states have experienced substantially faster growth in IP admission rates among pediatric patients with a primary mental health diagnosis compared to the rest of the US, albeit from a generally lower base. Increases in mental health IP admissions ranged from a low of 27% in the West North Central region to a high of 137% in the Middle Atlantic region.

Figure 3 illustrates regional variations in IP hospital admission rates for mental health conditions, which in 2021 ranged from a low of 18 patients in the Pacific region to a high of 65 patients in the West North Central region.

FIGURE 3: IP Utilization across Regions, 2016-2021

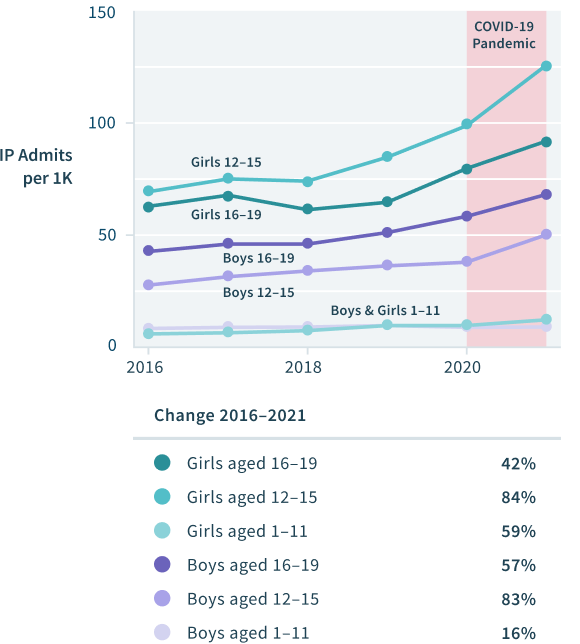

FIGURE 4: Annual Trends in IP Utilization by Age and Sex, 2016–2021

Figure 4 highlights differences in pediatric mental health inpatient utilization and growth by age and sex. Substantial increases from 2016 to 2021 are observed for both boys and girls of all age groups, but particularly among adolescents over 12 years old. Mental health IP admissions increased 84% among girls and 83% among boys aged 12–15 years old from 2016–2021. Underlying admission rates for girls aged 12–15, however, were around 2.5 times higher than admission rates for boys in the same age group across the entire time period.

IP utilization increased dramatically during the pandemic, with the largest increases for adolescents aged 12–15

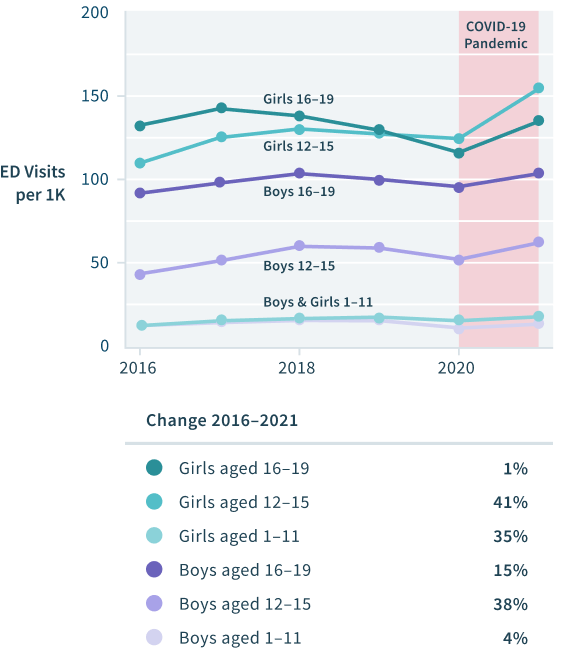

FIGURE 5: Annual Trends in ED Utilization by Age and Sex, 2016–2021

Figure 5 highlights differences in pediatric mental health ED utilization by age and sex. Girls were more likely than boys to experience an ED encounter. While ED utilization dropped at the beginning of the pandemic, rates have continued to rise more recently. ED utilization has risen significantly among 12–15 year-olds in the pediatric population with mental health conditions since 2016. Mental health ED visits increased 20% overall, ranging from a low of 1% for girls aged 16–19 years old to highs of 41% and 38% among girls and boys aged 12–15.

Girls and boys aged 12–15 experienced a sharp increase in ED utilization during the pandemic

FIGURE 6: Trends in IP, ED, and OP Utilization Rates by Payer

We found significant differences in mental health utilization according to health insurance coverage, as illustrated in Figure 6. IP admissions among children with mental health conditions increased by 103% among commercially insured children and by 40% among children insured by Medicaid from 2016 to 2021. Mental health-specific ED visits declined by 10% for children with commercial insurance and increased by 20% in the Medicaid population over the same time period. Finally, since 2016 MD/OP mental health services utilization has risen 32% among children with commercial insurance and declined 2% among children with Medicaid. The decline in MD/OP utilization, coupled with the increase in ED utilization for children with Medicaid, may point to issues around adequate numbers of mental health professionals accepting Medicaid patients.

Mental health IP utilization grew faster among children with commercial insurance than those with Medicaid

As shown in Figure 6, despite faster overall growth in the commercially insured population, overall levels of IP, ED, and MD/OP mental health services utilization have historically been higher among children with Medicaid. For the first time in 2021, IP utilization rates in the commercial population surpassed those among children with Medicaid. Mental health ED utilization among pediatric patients with mental and behavioral health conditions continues to be much higher among children with Medicaid, with utilization rates in 2021 nearly twice as high in the Medicaid population compared to children with commercial insurance.

We estimate that the severity of pediatric mental health conditions, especially when measured by acute mental health services utilization, has increased substantially from 2016-2021. The responsibility of addressing the trends presented in this brief fall to our health care leaders. In deciding where to focus efforts, organizations that share our concern for improving pediatric health and wellbeing may prioritize goals from the Healthy People 2030 initiative. In particular, it is imperative to increase mental and behavioral health screening rates for all children and to promote access to appropriate, evidence-based treatment for those with a diagnosis regardless of insurance coverage. These goals cannot be met by children and parents alone.

Improving access, utilization, and quality of pediatric behavioral health services should be a national priority for US health systems, payers, and policymakers.

Stakeholders across the pediatric care spectrum must also prioritize additional research to assess trends and share findings. More research is specifically needed to rigorously assess interventions that aim to improve pediatric mental health and wellbeing. We must urgently ramp up these efforts in the face of the general shortage of mental health care providers and the absence of integrated mental health care in many US primary care settings. The role of behavioral health services provided by school-based programs should not be overlooked and would benefit from additional state and federal support. The recent allocation of $3.5 billion in federal funding for behavioral health programs and the introduction of an around-the-clock 988 hotline for suicide prevention and mental health crisis services represent important steps forward to improve US mental health care access.